National flags, like national songs and sports and birds, don’t take hold of the imagination of a people unless they attach to something mythic. One of the most obvious and robust examples involves a man named Wilfred the Hairy. Wilfred holds a prominent place in the collective memory of the Catalans, those people living in and around Barcelona, many of whom have been trying in recent years to separate themselves from Spain. Their enthusiasm for Wilfred lies right at the intersection of truth and fiction. For them his life means the survival of a nation under threat; his death in the collective conscience would signal the completion of a cultural genocide. Who is Wilfred? By what special mystique do Catalans remember him when they wave their flags? And why is he hairy?

Let’s begin with the facts: Wilfred (Guifré el Pilós in Catalan) was a frontier overlord, a “count”, in the last years of the Carolingian empire. He belonged to a powerful family of Gothic extraction. In 870 C.E. (256 on the Muslim Hijri), he controlled the frontier counties of Urgell and Cerdanya, land below the Pyrenees Mountains in the frontier zone held precariously by Christians in the Frankish north against Muslim lords in the Iberian south. We know he was pugnacious and smart – always ready for a fight, but with enough tactical and political brilliance to keep from getting killed for a couple of decades (a long time to survive a warrior’s life in those years). He died in 897 defending Barcelona against the army of the Muslim Qasi rulers of Zaragoza and Lleida.

The real Wilfred succeeded in several important ways. By 878 he had taken possession of the counties of Barcelona, Girona, Besalú, and Ausona, thus bringing together the counties that came to be the core of the Principate of Catalonia. He confirmed the heritability of the title of count, which later counts of Barcelona, for good reason, would hold as a title greater than that of king. He also established a bishopric and a monastery that Catalans have used to great purpose over many centuries to confirm their identity. If you want details, and sources, see pages twenty-nine to thirty-three in my book Constructing Catalan Identity.

The Wilfred of legend makes even greater claims than the Wilfred of history to a pre-eminent place in the Catalan imaginary. Poets and writers, not only those of the nineteenth-century Catalan Renaissance, La Renaixença, but also earlier generations of storytellers and chroniclers, took a particular interest in celebrating, elaborating, and exaggerating his life and death, so that from some fragments of truth have grown much useful fiction. Paul Freedman has helped us identify two separate threads in a fabric of legends about Wilfred. Catalans I have talked to typically conflate some elements of the two folkloric traditions.

Of the two story threads that lead us to Catalan heraldry, and ultimately to the flags waved during the mass demonstrations held in Catalan cities in recent years, the first relates the rise of the young Wilfred. It indicates that his moniker “the hairy” derives from his return home after his exile as punishment for a vengeance killing – he murdered the murderer of his father. He had changed much from the experience of his long exile, and, because he was an outlaw, he had to make his return in secret to reclaim the rights to lordship lost at his father’s death. Still, upon his return home his mother recognized him immediately. As her fictionalized voice tells us from that time long ago, she knew something about her son that remained unknown to others: he had hair where other men do not have it (your guess is as good as mine about what she saw and where upon him she saw it). The mother watched as her son grew in political and military vigor, and then took his place as the frontier boss.

http://blogs.sapiens.cat/socialsenxarxa/2012/03/25/guifre-el-pelos-fra-joan-gari-i-montserrat/

By the late seventeenth century, collectors of such origin stories recognized that this one was a concoction, a fable meant to confirm emotional connections between a people, a place, and a past. Of course, that did not at all reduce its usefulness as a compelling and curious vehicle through which Catalans could learn about personal and corporate identity, defense of lineage, Christian virtue, and the hero’s journey.

The story of Wilfred’s exile and return to reclaim lost rights is not the most important instance of Wilfred mythology. A more significant legend about him has to do with the details of color and line that became the essential symbol of Catalan nationality, the Catalan flag called the Senyera.

The Christian Frankish descendants of Charlemagne had nominal control of the frontier areas managed for them by Wilfred and others, but they had begun to lose their grip on this so-called Carolingian March (blaming Muslims, here as elsewhere, is shortsighted – Muslim, Viking, and Magyar raids merely took advantage of a weak Carolingian state imploding under the weight of the hubris of its leaders). Wilfred, as a regional count in the service of the Frankish monarch, prepared to engage in battle against his Muslim foe, and he called upon the Frankish king for aid. Wilfred met the enemy before the king arrived. And when the king finally did appear, Wilfred lay bleeding, suffering a grave wound to his chest.

The story up to this point has some basis in fact. Wilfred’s expansion of his territory, building fortified towers deep into contested territory in the County of Ausona, drew a response from the Banu Qasi rulers of Zaragoza and Larida (present-day Lleida). In 884, Ismail Ibn Musa repelled an attack by Wilfred’s troops at Larida. The great historian Ali Ibn al-Athir described the encounter, correctly it seems, as devastating to the Christian side. In 897, Ismail’s successor, Lubb Ibn Muhammad Ibn Musa, attacked Barcelona. Wilfred died in that second encounter.

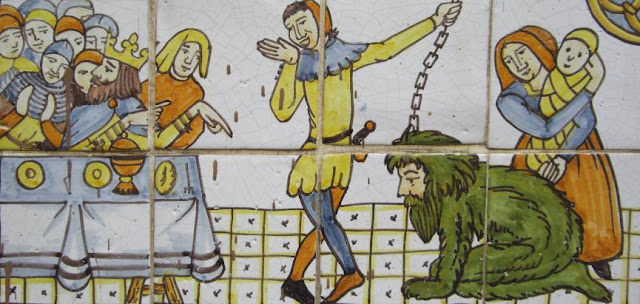

The direction taken by myth now departs from the truth: Blood poured from Wilfred’s chest as the king approached him. The king is Charlemagne in some tellings, Louis the Pious or Charles the Bald in others – in actuality, all died before Wilfred’s time. Regardless of which king stands in, the story has it that the king felt the sting of shame at arriving late to the encounter. In astonished admiration of Wilfred’s selfless defense of his Christian people, the king made the decision in that moment to give the frontier region in perpetuity to Wilfred’s successors. This, according to Catalan collective recall, is the moment of Catalonia’s independence (from what would become France—this is, by the way, long before Spain became Spain, and a very long time before Catalonia became part of Spain in 1412 or 1469 or 1486, depending on how you count). The king signaled the perpetuity of his compensatory gift by plunging his hand into Wilfred’s bloody wound and drawing it over the count’s golden shield, thereby creating the symbol of the newly independent lands: the four crimson stripes on a yellow background that signify the Catalan lord, lands, and people.

Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi (1844)

https://www.racba.org/es/mostrarobra2.php?id=408

Pere Anguere identifies one of the single most important attributes of this tale when he says that “the origin of the story is lost in the clouds of time.” Unlike the flags of France and Spain, England and Italy, and even the Basques, whose histories are solidly known, the history of les quatre barres (“the four bars” in English) remains mysterious. As such, it remains open to elaborate retelling. However, despite the variants, what has remained constant is that, since at least the thirteenth century, these red and yellows bands have been the official Catalan insignia, borne on coats of arms and waving as the flag, or Senyera.

Wilfred’s mythic ingenuity made Catalonia an independent nation. And more, according to legend, he shed his own blood to give Catalans their national heraldic symbol.

One thought